Francis MacNeiss McNeil McCallum, better known as Captain Melville, is one of Australia’s most intriguing bushrangers. He at once bears the tropes of the traditional bushranger – a charming, adventurous highwayman and escapologist with a flair for drama – while also being something unique. His story is one punctuated by misadventure and violence and ends gruesomely.

McCallum was born in Inverness, Scotland, in 1822. On 3 October, 1836, he was tried in Perth for housebreaking. While he was on trial he admitted to having served 22 months in gaol for thievery prior, starting his criminal career at the age of 12. Found guilty, he was sentenced to 7 years transportation but was forced to serve almost two years in prison in England as Edward Mulvall before he could be sent out. On 25 May, 1838 he began his journey with 160 other convicts to Australia on the Minerva, and on 28 September 1838 he arrived in Van Diemens Land. The sixteen year-old McCallum”s sentence was to be served at Point Puer boys’ prison at Port Arthur. Point Puer was a landmark in British history as the first juvenile prison. Prior to this all convicts, regardless of age, were kept together and in the same conditions. Given that under British law a child as young as 8 years old was able to be tried as an adult, this resulted in many children being brutalised alongside hardened criminals and adult offenders. Point Puer provided an environment for wayward youths to learn skills and a trade, with emphasis on trades such as shoemaking, timber work, masonry, gardening and construction. McCallum served 18 months at Point Puer whereupon he was assigned to the timber yards in Hobart. It was here that McCallum first took to the bush, taking another boy named Staunton with him. They were quickly apprehended and sentenced to 5 years at Port Arthur where McCallum promptly received 36 lashes. This would not be the last time.

On 20 September, 1840, McCallum was absent from work and displayed insolence towards his guards, receiving 20 lashes. Later that year his insolence got him another 36 lashes and 7 days in solitary. On 22 February the following year his misbehaving saw him slapped with an additional 2 years into his sentence. During this time he was given 12 months probation during which time he performed a burglary that saw his sentence amended to transportation for life.

For the next few years McCallum continued to be a fly in the ointment of the authorities. He was frequently flogged and frequently absconded, apparently spending time in local Aboriginal camps, resulting in months and months added to his sentence and most of that in leg irons. By the end of 1850 McCallum had finally made good his escape, and now as a scarred and bitter 27 year-old, he made his way to the mainland and assumed the name Edward Melville.

Since the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851, the population had exploded and with this came increased struggles and conflict. The Australia McCallum found himself in was one where there was particularly huge conflict between Europeans and Chinese immigrants, usually over gold claims. The difficulty in mining enough gold to make a living was enormous and thus tensions were high. The goldfields were subject to riots, lynchings, murder and robbery. The villages on the goldfields were rudimentary but diggers were still able to satiate their vices. The police force was largely staffed with ex-convicts who were paid embarrassingly meagre wages with bonuses for arrests. This resulted in widespread police harrassment and lots of questionable arrests. Such a hotbed of tension and corruption was perfect breeding ground for bushrangers.

As with most prospectors, McCallum did not fare well on the diggings and sought alternative means of supporting himself. He set his sights on the highways and plunged into the dangerous career of highway robbery. In 1852 McCallum went bush, adopting the moniker, “Captain Melville”. Operating between Melbourne and Ballarat, particularly in the vicinity of the Black Forest and Mount Macedon, Captain Melville gained a reputation as a man not to be trifled with.

It was during this time that a story oft attributed to Melville was supposed to have taken place. As the story goes, Melville rode to the station of a squatter named McKinnon as the sun was setting and let himself in. He summoned the maid then asked to see the man of the house. When McKinnon responded, Melville stated that he had heard the man’s daughters were accomplished musicians and requested an impromptu performance. McKinnon protested that the girls were dressed up ready to go to a ball that evening and refused to summon the girls. Melville levelled his pistol at McKinnon who quickly reconsidered his answer. The girls were brought down and compelled to play piano with Melville singing along. However, word had reached the local constabulary and by dawn a party of troopers was on the doorstep. Melville, quick as a hare, made a hasty exit via a window.

On 18 December, 1852, Melville, in company with a mate named William Roberts, stuck up Aitcheson’s sheep station near Wardy Yallock. After rounding up the sixteen staff and imprisoning them in the barn, Melville bailed up Wilson, the overseer, and Aitcheson then added them to the prisoners. After Melville cut a length of rope into pieces, they proceeded to call the men out one by one and tie them up to the fences outside. When Wilson asked what they wanted, Melville replied, “Gold and horses, and we are going to get them.” With the men secured, the bushrangers went to the homestead. Melville told the women not to fear them as they would not interfere with women more than necessary. He then ordered them into a room and instructed them to prepare food, which was taken with two bottles of brandy to the men. Melville and Roberts indulged in a meal themselves then ransacked the house, taking any valuables they could grab. After this, the pair stole two of Aitcheson’s finest horses and gear then, as they were leaving, they informed the prisoners that Mrs. Aitcheson would be down to untie them once the coast was clear.

Melville and Roberts took up residency on a spot on the Ballarat road where they could stop travellers on the way to and from Geelong. The day following their raid on Aitcheson’s farm, the pair struck again from their new spot. Two diggers, named Thomas Wearne and William Madden, were bailed up on the Ballarat road. Melville and Roberts took £33 from the pair before asking where they were headed. The victims stated that they had been heading to Geelong to spend Christmas with friends, but now they would have to go back home as they had no money. After a brief consultation, the bushrangers returned £10 to their victims and hoped it would enable them to enjoy the festive season.

The takings were good on the Ballarat road in the lead up to Christmas as travellers went to and fro with the intention of visiting friends and family for the holiday. Soon a reward of £100 was issued for their capture. Their last victim on the road was bailed up at Fyans Ford, five miles from Geelong, on Christmas Eve. After completing the transaction, the bushrangers rode into Geelong and booked in at a hotel in Corio street where they had their horses attended to. Elated by the recently ill-gotten gains and seemingly feeling in the Christmas spirit, Melville and Roberts went to a house of ill-repute nearby to spend Christmas Eve indulging in wine, women and song.

The booze must have loosened his lips as much as his breeches for when he was engaged in the affections from one of the girls he let slip who he was. The women promptly kicked into action, keeping the bushrangers occupied while one of them snuck out to alert the police. Melville, despite being drunk, became suspicious of the women and ordered Roberts to fetch the horses. Roberts, however, was passed out drunk on a table. Unable to rouse Roberts, Melville decided to cut his losses and bolt. When he opened the front door he saw the working girl entering the front gate with police. Slamming the door shut, Melville raced to the back of the house, smashed open a window with a chair and jumped out of the window. He ran across the yard and hurled himself over the fence, knocking over one of the constables that was arriving to apprehend him. Barely breaking his stride, Melville continued to run through a vacant lot, but changed direction when he realised that the police lockup was between him and his horse. He continued to run, with police in pursuit, towards the old dam where he came across a young man named Guy who was returning from a ride on a horse he had borrowed from his lodgings at the Black Bull Inn. Melville saw his chance to gain a mount and yanked Guy out of the saddle. Guy was quick as a flash and returned the favour, copping a punch while restraining Melville. In moments the police arrived to properly arrest their target. They complimented the civilian on his having pinned the fugitive down. Guy simply replied that he wasn’t going to lose a horse like that.

Melville and Roberts were licked – their lucky streak officially at an end. They were imprisoned in the South Geelong gaol, then conveyed by dray to the courthouse, while heavily manacled. They were surrounded by police and had no hope of escape. The trial was speedy, and Melville and Roberts were convicted on three charges of highway robbery. Melville was sentenced to thirty two years hard labour: twelve years for one crime, ten apiece for the other two.

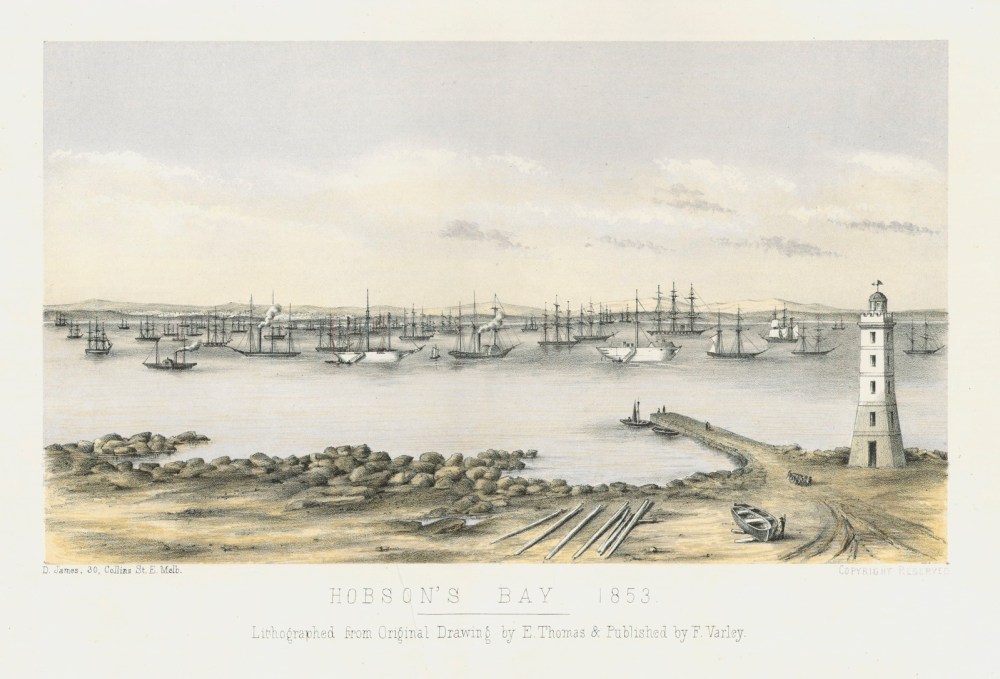

Melville was sent to do his time on the prison ships moored at Hobson’s Bay, Williamstown. These imposing maritime structures were referred to as hulks, but were actually converted cargo ships that had been abandoned by sailors who ditched their jobs to strike it rich on the goldfields. Now, rather than hauling goods they were places of incarceration as well as cruel and unusual punishment. McCallum was imprisoned on President, the place reserved for the worst of the worst, on 12 February, 1853. Here inmates were frequently denied all comforts, including the ability to read the Bible, and were often subjected to a myriad of inventive and inhumane punishments in response to misbehavior. This was not enough to quell Melville’s insatiable appetite for rebellion and on 26 January, 1854, he was given a month in solitary confinement in heavy irons for attempting to incite a mutiny.

Melville was transferred to Success in February of 1856. Success was lower security, and in addition to now being taken to the shore to work in the stone quarry, Melville managed to pick up a job translating the Bible into Indigenous languages, which he claimed to speak fluently. It was honest work, even if the person doing it wasn’t equally as honest.

On 22 October, 1856, things took a startling turn. As the launch boat was towed from Success carrying fifty convicts to the stone quarry for the day’s labour, the convicts began to push forward, crowding the bow. Jackson, the overseer, ordered the men back, but the orders were disregarded and a group of the convicts grabbed the tow rope, pulling it until they brought the launch close enough to the tugboat to enable transfer. Ten of the convicts jumped across: Melville, John Adams, Matthew Campbell, Henry Johnstone, Patrick Ready, Terence Murphy, John Fielder, Matthew McDonald, Richard Hill, and William Stevens (alias Butler).

Jackson tried to force the prisoners back as they began leaping into the tugboat but he was struck and fell into the water. At that moment things spun out of control. The guards on Success began firing at the mutineers, one of the shots hitting Richard Hill in the neck. Corporal Owen Owens, a seaman attached to Lysander, was struck by Melville and thrown overboard by two other mutineers. The blows continued to rain down as he attempted to climb back in. Several prisoners, including Melville, attempted to hold him under the water until a blow from what was believed to be a mallet or a boat-hook penetrated his brain, killing him. The mutineers would state that it was Stevens who had struck the lethal blow using a mallet that had been smuggled on board to break their chains with. The instrument was thrown overboard. One of the rowers, John Turner, was also plunged into the bay as were James Hunter of Lysander, who jumped into the water out of fear, and Peter Jackson, the ship-keeper for Lysander, who was turfed out but had managed to rise to the surface of the water in time to see the tail end of the struggle. The rowers realised that it would be folly to resist and dishonorable to comply with the mutineers so they evacuated. The mutineers took control of the tug boat. Melville stood triumphantly on the tug, apparently brandishing the mallet. One of the mutineers, Stephens, at this point exclaimed “All is lost!” He then jumped off the boat into the water, leaving the others to their fate. The irons around his ankles caused him to immediately drown.

The mutineers attempted to steer the boat towards a cluster of cutters (fishing boats) near the shore but were unable to reach them. Melville playfully blew a kiss to Thomas Hyland, the chief warder of Success, as they began to make good their escape. Instead of heading for the cutters they changed course, hoping they would eventually be able to row downstream in the river. The escapees were soon intercepted and captured by a police boat. When the corpses of Owens and Turner were fished out of the water, Turner appeared to have drowned, but the coroner stated that Owens had a hole in the left side of his head that was big enough to fit three fingers into. In the recovered boat Tristram Squire, the shipkeeper of Success, found two makeshift knives made out of and old pair of sheep shears.

Melville was tried in November before Justice Molesworth. While the other mutineers were acquitted of murder by construction on the 26th, owing to Owens’ death not being clearly a result of the escape plot, Melville had the charge of murder lumped squarely upon his shoulders. As was usual by now, Melville defended himself, charged with murdering Owens. Melville argued that as the warrant for his detention referred to him as Thomas Smith, which was not his name, he was being detained unlawfully. The session concluded at midnight with the jury finding him guilty, but it was not unanimously agreed upon that it was he that struck the killing blow, bringing into question the extent to which he could be charged with murder. In his closing speech to the jury, Melville went to pains to disclose the injustices he felt had been perpetrated against him, claiming he had been bullied, beaten and oppressed by corrupt prison staff, leading him to such desperation that he would be prepared to kill in pursuit of freedom. Melville’s attempts to defend himself were in vain, however, and on 21 November, 1856, he was sentenced to death.

Melville was returned to Success to serve out his sentence. Such was his desperation that he began to act completely unruly either to be transferred off Success, presumably to a lunatic asylum, or to be given the sweet release of death. When he attacked a guard, almost biting the hapless man’s nose off, he was given solitary confinement. Needless to say this was less than adequate and Melville continued his depredations in captivity.

Melbourne Gaol was to be Melville’s home for the remainder of his life. The prospect of thirty-five years in prison was not a life that Melville was willing to endure. His behaviour became erratic and uncontrollable, frequently refusing food. On one occasion in July 1857, Melville attempted to stop the prison guards from removing his night tub from his cell in order to clean it. He armed himself with a sharpened spoon and the lid from the tub as a shield and threatened to kill anyone that attempted to removed the night tub. During a scuffle with three of the guards, Melville attacked the governor of the gaol, George Wintle, and cut his head open behind his ear using the sharpened spoon. After this Melville was restrained and kept in solitary confinement where he could be monitored and assessed for mental illness. It was assumed that Melville was feigning madness in the hope of getting relocated to Yarra Bend Asylum so he could escape.

Melville was clearly despondent and sought the ultimate escape. On 11 August that year, when Melville failed to respond to the turnkey, guards entered his cell to find him dead. There was blood and foam coming from his ears and mouth, his face was contorted and there was a coiled handkerchief tightened around his neck. It was later determined that Melville had crafted a makeshift rope put it around his neck as tight as possible then simply slumped his head to the left until he was strangled to death. Prior to this he had scrawled a message on his wall in pencil declaring that he would leave the world on his own terms. An inquest deemed the death a felonious suicide. Melville’s body was buried in the prison grounds in an unmarked grave. In the end, it seems, Melville finally got the defiant freedom he had craved since he was a boy convict.

Having embarked on some research for a year 5 Gold Rush assignment on Bushrangers-Captain Melville in particular,

your writing has proven to be the most highly detailed and accurate telling of Melville’s tragic life.

Reading in Trove how long that list of offences was and how dreadfully he tells of his treatment, I’m surprised he had the strength to even attempt escape.

Thank you for the care and attention you have taken in telling his story.

Thank you so much, Sarah. The information I provide on the site is not an exhaustive account, but I do try my best to be as accurate as possible with the information at my disposal. There’s a lot of myths about Melville (many he started himself) so it can be hard to sift through fact and fiction sometimes. I wish you all the best in your future adventures in historical research!