It is well known that the story of the Kelly Gang is the bushranging tale most often depicted in film (only rivalled by adaptations of Robbery Under Arms). Depictions of Ned Kelly in media are so numerous that it would be almost impossible for one person to document them all. Given less attention, however, are the other members of the gang. Of the three other gang members, only Joe Byrne’s story has been documented in any considerable detail. Byrne is generally considered to be Ned Kelly’s right hand man and most people only know his story as it relates to Ned Kelly. Joe is a mainstay of film adaptations of the Kelly saga, unlike his best mate Aaron Sherritt, and thus we have a wealth of sources to compare and evaluate.

Because of the sheer volume of Kelly movies dating back to the silent era, there is a daunting task in evaluating all of them in terms of their accuracy to history, so for the sake of this article we will only be looking at the four of the most recent examples:

* Ned Kelly (1970) featuring Mark McManus as Joe Byrne.

* The Last Outlaw (1980) featuring Steve Bisley as Joe Byrne.

* Ned Kelly (2003) featuring Orlando Bloom as Joe Byrne.

* True History of the Kelly Gang (2019) featuring Sean Keenan as Joe Byrne.

These portrayals will be reviewed based on how they are written and overall creative choices. This will allow us to see what works and what doesn’t in each version, based on common criteria. Given the number of portrayals that will be looked at, this will be a bit longer than most articles in this series.

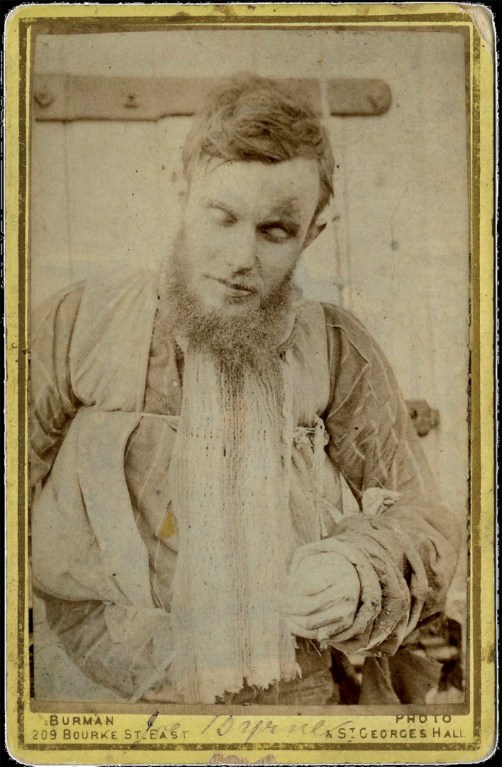

Physical appearance and mannerisms

The 1970 depiction of Joe Byrne has a reasonably close physical resemblance to the historical Joe, however he is clearly a man in his thirties. McManus’ Joe has brown hair, a stubbly beard, and blue eyes. His clothing is quite odd. He favours worn down bush clothes with muted colours, as well as a big floppy hat and tall lace-up boots that appear to be 20th century army boots. After raiding the hawker’s wagon he wears a black hat, high heeled shoes, and light coloured plaid suit. He is also occasionally seen with a velvet waistcoat and a brown scarf. This Joe speaks with a nasally Irish brogue, and tends to range in temperament from high energy and playful, to snappy and brooding. He has a fondness for an old-fashioned pint of ale, but does not exhibit any other particular vices.

The 1980 Byrne is the most physically similar on the list to the historical Byrne. He has a long face with large, protruding ears, blue eyes, coppery hair, full beard and light moustache. Again, he looks to be in his early to mid thirties. This Joe favours more fashionable clothes in blues and browns, and is particularly fond of flares, high heeled boots with spurs, light coloured shirts and waistcoats. His signature item of clothing is a hat with a flat crown and very wide brim that curls slightly. He can also occasionally be spotted wearing a ring on his left hand. This interpretation of Joe speaks with a mongrel accent that is mostly Irish, but occasionally slips into something Australian. He is often quiet and thoughtful, though he has bursts of exuberance and joviality, and can be very passionate and hot-tempered. He is frequently seen smoking a pipe, and sometimes drinks liquor. At Euroa he nabs himself brown flares, a brown jacket and a blue waistcoat with brown lapels. He can speak Chinese and is seen to negotiate with a gold merchant.

Orlando Bloom’s Joe is very sober in appearance and manner. He appears to be the right age, with dark brown eyes, a mop of curly black hair and wispy black facial hair. This Joe is seen briefly wearing a sort of Homburg hat, and usually favours fashionably cut clothes in black and dark greys with cowboy boots. During the Euroa robbery he sports a light grey tweed suit, which gives him a much friendlier appearance. At Glenrowan he favours black garb, a long greatcoat and a white knitted scarf. He is occasionally spotted wearing a large silver ring with a black stone set in it. He rarely smokes or drinks, and generally has a quiet, melancholic temperament when not trying to seduce women, to whom he seems to be irresistible. He can speak Chinese, and uses it to seduce a Chinese servant. He talks softly with an Irish brogue, but prefers to stay quiet.

In the 2019 interpretation, Joe is presented at first as a highly excitable dullard, and possibly homosexual, speaking with a broad Australian accent. This continues to be the case throughout the production, but he becomes increasingly prone to nervous breakdowns and zoning out. After the Stringybark Creek incident he tries to convince Ned to escape to America with him so they can eat donuts. He smokes opium almost constantly and is occasionally shown to be so completely stoned that an ember landing in his eye doesn’t register to him. Keenan strongly resembles the historical Joe physically, excepting his long, blonde hair. In terms of clothing, nothing he wears is period accurate. He is shown wearing a brown duffle coat and chinos, or tight shorts, cowboy boots, an Akubra and a cardigan with no shirt underneath. At Glenrowan he wears a pink dress with black and white face paint. He tends not to get involved much in Ned’s scheming, except at Stringybark Creek where he tries to dissuade Ned from attacking the police camp. His temperament generally ranges from childlike enthusiasm to haunted and morose.

The real Joe Byrne was only in his early twenties when he became mixed up with Ned Kelly. He stood just shy of six feet tall, and was well-built with long, delicate features, large ears, pale blue eyes, coppery coloured hair and usually wore a full beard and wispy moustache. He favoured fashionable clothing, especially flared trousers, high-heeled boots and was known to wear a felt hat with the crown turned down. At Euroa he scored a new outfit of elastic-sided boots, brown trousers with matching waistcoat, a grey coat, black tie and a Rob Roy shirt. Occasionally he was seen wearing long boots with long-necked spurs. At Glenrowan he wore brown trousers and waistcoat, a great striped Crimean shirt, blue sack coat and a tattered scarf. He notably wore rings taken from Constables Lonigan and Scanlan. In terms of personality, he could be warm and friendly, usually quiet and reserved, and was known to be very tender with women. On the flip side, he could be quick to rage and became violently angry when pushed. He smoked tobacco frequently, and was known to be addicted to whiskey and opium. Some reports describe him having a peculiar swagger when he walked. Like most young men of his generation, he spoke with an Australian accent and used Australian slang (the accent has been recorded as far back as the 1850s). He spoke in a “clipped” fashion, which probably meant that he tended to drop letters off words (eg. drinkin’, smokin’), or spoke in short bursts.

Relationship with Aaron Sherritt

Perhaps the most important part of Joe’s life was his relationship with Aaron Sherritt, his lifelong mate. It was his connection to Sherritt that stood to potentially jeopardise the gang’s freedom and liberty.

In the 1970 film, Joe and Aaron have just gotten out of prison and are looking for work. Their relationship is clearly one of two friends who are joined at the hip. When together they seem to have boundless energy and muck around. When Joe learns of Aaron’s betrayal he does not hesitate to assume Aaron has sold him out in order to afford new clothes. There is no internal conflict about what to do to him.

Aaron and Joe in The Last Outlaw are more like brothers. Joe trusts Aaron completely, and it takes a great deal of convincing to get him to accept Aaron’s betrayal. When he does, it boils over into an unquenchable hatred. In this version it is clear that Aaron is trying to confuse the police to help his mates, with Joe being in on it. This serves to make the collapse of their relationship all the more tragic and accurate.

The 2003 iteration has much the same dynamic as the 1970 one, except that Aaron and Joe have been friends with Ned since they were teens so it is more of a three-hander. Joe doesn’t appear to be any closer to Aaron than anyone else. The revelation that Aaron has betrayed them simply makes Joe sad, and he is left questioning why he did it.

In True History of the Kelly Gang Aaron Sherritt is never included, which only serves to push Joe further into the background and make things all the more about Ned.

In reality, Joe and Aaron had known each other since they were very young. They were pretty much inseparable from that time, and did everything together. They both worked with Ned stealing horses, but for some unknown reason only Joe was present at Stringybark Creek. However, Aaron vitally provided shelter and protection in the immediate aftermath, then acted as a double agent to keep the police distracted while the gang moved around. It is probable that Joe knew of this in some regard, which is why he tested Aaron’s loyalty repeatedly when faced with rumours of his treachery. This makes Joe’s anger and subsequent willingness to murder Aaron make more sense, for such a betrayal would have had far more meaning.

Meeting Ned Kelly

The first time Joe met Ned Kelly is a mystery. There is much speculation, but it remains simply that.

In the 1970 film, Joe and Aaron meet Ned at the sawmill where he works when they are fresh out of gaol and looking for jobs. Immediately the trio have a rapport, with Ned declaring that despite there being a lack of work he had best look out for his own kind, suggesting that he will find jobs for them. Indeed, later on we see Joe shifting lumber at the sawmill when Constable Fitzpatrick arrives to question Ned about his brother.

This is almost identical to the how the meeting is depicted in The Last Outlaw. Where this version differs is that Joe and Aaron are introduced to Ned by his brother Jim, the three of them having supposedly just come out of gaol. This time the sawmill is packing up to go to Gippsland, so instead they then join Ned in mining for gold and Joe teaches him how to build sluices.

In the 2003 film we do not see the meeting, Ned is already a friend of Joe and Aaron, demonstrated by the three of them napping together under a tree in the very first scene of the film. Joe and Aaron are next seen waiting for Ned as he leaves gaol. It is indicated that Joe is a family friend and has been checking in on Ned’s family while he was in gaol. There is no indication that they worked together.

In the 2019 film, we first see Joe when he is working as Ned’s boxing promoter. He collects the bets and hypes up Ned’s boxing match, calling him a “dancing monkey” to get him revved up. It is clear that there is a strong bond between the two.

Of course, this is an area of history that is unrecorded, so to write about the meeting is pure speculation. That said, there is no indication in any recorded history that Joe or Aaron ever worked with Ned at a sawmill, and as Ned was only ever involved in one boxing match we know of, which took place before he knew Joe, it is unlikely he would have needed a promoter. Moreover, the earliest that we know of Joe and Aaron being associated with Ned is 1877, when they helped him steal, shift and sell horses. However, Joe and Aaron could have met Ned as early as 1876, when they were in court at Beechworth on the same day as Dan Kelly, meaning they may have waited in the holding cell together. Ned was present as a witness for Dan, so this may have provided am opportunity for their paths to cross. We will never know for sure, but we can guess based on available information, and on that level The Last Outlaw gets the closest to the truth on this point.

Opium use

In True History of the Kelly Gang, Joe is frequently seen smoking opium from a special pipe (seemingly a 19th century Chinese water pipe). The historical Joe’s opium habit is well known. He is often described as an opium addict, though the extent to which he used the drug is unknown. What is known is that he sourced it from the Chinese in Sebastopol, which is where he was spotted buying it by a police spy. Of course, to suggest that Joe smoked it very occasionally as a recreational drug would not have fitted with the grim and gritty story Justin Kurzel wanted to portray, so this version of Joe is rarely straight.

None of the other productions even hint at opium use. At most we see Joe smoking tobacco from a pipe or perhaps a cigar. It could reasonably be argued that this was entirely down to content standards for film and television in the ’70s and ’80s, but as the opium use was not well known at that time it may have simply been that it wasn’t considered. As for the 2003 film, no doubt it was about not only time constraints, but also the connotations that come with a main character using narcotics.

Romance

In the 1970 film, Joe is never shown mingling with the opposite sex. There is no indication of any romance at all.

In The Last Outlaw and the 2003 film, his love life is portrayed rather accurately. In the former he visits his girlfriend at night at the Vine Hotel in Beechworth where she is employed as a maid. Though here her name is Helen, in all other respects she is identical to the historical Joe’s girlfriend. In the 2003 film his girlfriend is a barmaid named Maggie who he occasionally visits. In both portrayals she is the one that convinces him Aaron is betraying him. In reality, Joe’s girlfriend was indeed known as Maggie, though this was supposed to have been a pseudonym, and her supplying of information to Joe about Aaron proved important to what eventuated only a few days later in the lead up to the Glenrowan siege.

Where the 2003 film veers from known history is in Joe’s promiscuity. He is portrayed as a lothario who can pick up any woman he wants. He seduces Mrs. Scott at Euroa and Julia’s servant girl when he is in the bath. Though there are accounts of Joe’s life that state he was popular with the ladies, who gave him pet names like Sugar and Little Birdy, there were no definitive sources that claimed he went from pub to pub seducing barmaids or anything of that sort. It is reasonable to suggest he had romantic dalliances with women like Mary Jordan, a barmaid near Jerilderie, and Ellen Byron, his teenage sweetheart who was also a sympathiser, but it is only speculation.

The 2019 film it is heavily implied he is either in a romantic relationship with Ned Kelly or desires to be. Their physical intimacy in particular is on the nose in this regard.

Horse Stealing

In 1877, Ned Kelly set about getting back at the squatters who he had taken exception to, stealing their horses and selling them over the border for profit. This is usually a staple of adaptations of the story to film, but not always.

In the 1970 film, Joe and Aaron are eager participants, joining Ned and his stepfather George King in the trade. In one scene we see Ned negotiate horse prices with William Baumgarten by playing a match of hop-step-jump in the rain. Joe and Aaron eagerly act as adjudicators, measuring the distances. They also stick with Ned after King departs, helping him paint horses so they appear piebald in order to disguise them for sale.

In The Last Outlaw there are more people helping out with the horse stealing racket, including Wild Wright, Tom Lloyd, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. This portion of the story is portrayed as if it were a great adventure with the men frequently sitting around in camp talking about how what they are doing is an affront to their enemies from high society. Eventually everyone leaves apart from Ned, Joe and George King, though King eventually does part ways with them on a river boat. Oddly, we see very little of the actual stealing and selling of horses.

The 2003 film portrays the horse stealing through a montage, where the horses are taken at night and sold discreetly. It is very similar to the sequence in the 1970 film, but instead of a jaunty, cheeky vibe there is more of a sense that this is an uplifting moment. The horse stealing is conducted by Ned, Joe, Aaron, Dan and Steve, as George King is not featured in this film.

In the 2019 film the horse stealing is conducted by George King, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart. Joe is uninvolved. Instead, while the thievery is going on Joe is mostly camping with Ned and getting stoned.

This is the part of the history where we get our confirmation of Joe and Aaron being associated with Ned. Aaron would later brag about their exploits to Superintendent Hare. At this time Joe used the alias Billy King, which was at one time misreported as George King.

Stringybark Creek

The 1970 and 2019 films don’t spend a lot of time at Stringybark Creek. The former presents it as a musical sequence, the latter reduces it to a couple of minutes rampage with dizzying camera work. Neither of these does a good job of portraying Joe’s involvement.

When one takes time to break down the Stringybark sequence of the 1970 film we see Joe portrayed as Ned’s follower, but also somewhat twitchy and uncertain. He is shown shooting Scanlan with a rifle as the constable struggles to get to his feet. This is obviously Ian Jones’ influence as it was he that championed the notion that Joe was the one that killed Scanlan. By the time Ned brings Kennedy down, we see that Joe is particularly disturbed by the turn of events and appears quite rattled. It is Joe who tries to convince Ned to leave the sergeant to die, clearly afraid to remain at the site of such a horrific crime. As far as appearances are concerned, Joe is here presented as disheveled and wearing a waistcoat and shirtsleeves, and no hat, which is a far cry from how he presented to Constable McIntyre.

The 1980 miniseries took time to build up to Stringybark, showing Joe joining Ned and following him to the police camp out of loyalty. Joe also hands tea to a visibly shaken McIntyre, which is accurate. In fact, McIntyre made a point of noting Joe’s kindness to him in order to emphasise the point that despite treating the constable with apparent empathy, when it came down to it Joe was willing to kill the man in order to demonstrate his loyalty to Ned. Once again, Joe is depicted landing the killing blow on Scanlan, this time with a pistol. This is later used to suggest that Joe continuing to stay with Ned is because he murdered one of the police, despite there being no difference in the eyes of the law at the time between one of the gang killing, or all of them. According to McIntyre’s evidence, Scanlan was shot by Ned Kelly, causing him to fall from his horse with blood pouring from under his arm. This is consistent with the wound identified as having brought about his death due to puncturing both lungs. In this case, even if Joe had fired one of the two other shots that hit Scanlan, which struck his hip and shoulder, it was still Ned Kelly that killed him. It would seem that Ian Jones preferred the idea of Joe killing one of the police in order to take some of the heat off Ned and help reinforce his own bias against Joe.

In the 2003 film, Joe follows Ned’s lead, as in the other depictions, but does not exhibit any notable compassion or kindness towards McIntyre. His head is very much in the game, and it seems that he and Ned are both calling the shots. Joe does not exhibit any remorse or fear, but rather a steely determination. He is armed with a snub-nosed revolver, which is a far cry from the old fashioned rifle with a large bore that McIntyre described him with. When Kennedy and Scanlan arrive, Joe engages in the gunfight with complete coolness, but notably doesn’t actually shoot anyone.

True History of the Kelly Gang shows Joe trying to convince Ned to go around the police, but to no effect. We also see him immediately traumatised by the violence Ned inflicts on the police, breaking down in tears and sobbing. It seems that in this incarnation, Joe was the only gang member with any empathy. The sequence is so fleeting that there is not much to pick from it.

Euroa

The Euroa sequence in the 1970 film is played as a farce, with jaunty music and comedic, campy moments played up for effect. One example of this is the gang in sped up footage walking around behind a hawker’s wagon then emerging out of the other side fully dressed in new clothes. In this depiction Joe and Ned go to the bank alone and while Joe is emptying the drawers and the safe, Ned bails up the manager and his family. This is a very amusing sequence, but only resembles the history in broad brushstrokes.

The Last Outlaw remains the most accurate depiction of Euroa, with only very minor details that stray from recorded fact, including Joe’s new outfit which was almost completely different from the one depicted. Notably, we see Joe guarding the prisoners at Younghusband’s Station on his own while some of the men inside conspire to break free, which is correct. Joe remains fairly quiet throughout proceedings, which is also accurate, though we don’t see him interact with Mrs. Fitzgerald as he did in reality. Overall, there is nothing especially deserving of criticism in this depiction.

In the 2003 film, however, Joe is present at the bank during the robbery. In fact, he even manages to seduce Mrs. Scott in the process. The gang’s use of Younghusband’s Station as a headquarters is entirely omitted, and many of the moments portrayed are incorrect, but it still maintains a sense of the farcical nature of the raid that was embodied in the 1970 film.

True History of the Kelly Gang completely omits the Euroa robbery from the story. It is possible this was due to time constraints, but given the importance of the robbery in the story, its absence is important. It was during the Euroa robbery that Steve Hart was finally identified as one of the gang members, Joe having been named a short time prior after the connection to Aaron Sherritt had been established (the gang having visited him shortly after the police killings and made their presence known with gunshots). It was this event that began to change perceptions of the gang in the public eye.

Jerilderie

In all productions Jerilderie is delivered in a truncated form. As this event took place over multiple days, it would take considerable time to portray all aspects of the affair on screen.

In the 1970 film, Jerilderie is presented as part of the musical montage, resuming after a brief narrative pause. Here we see the entire gang in police uniforms and it is Ned and Joe who rob the bank in disguise as policemen. We also see Ned and Joe take the gang’s horses to the blacksmith. Throughout the sequence Joe remains quiet except for when bailing up the bank manager in his bath.

Once again, The Last Outlaw nails this sequence. It is almost exactly as it happened, albeit in a streamlined depiction that leaves details out. We see Joe getting the gang’s horses shod by the blacksmith and charging the work to the government account, as well as assisting Ned in scoping out the town dressed in a police uniform. Joe is also the one that initiates the bank robbery after entering through a side door, which is correct given that the Jerilderie bank was connected by a corridor to the pub where the gang were holding their prisoners. In this scene, Joe is very much in command until Ned arrives to take over. As the events unfold, Joe seems to be enjoying the escapade immensely. When we see the gang taking breakfast, and Ned makes a point of emptying the bathtub, we see Joe pulling faces at the children in the background. This flash of silliness is clearly a creative choice by Bisley, and not based on anything from history, though it is amusing.

The 2003 film cuts out nearly the entire Jerilderie raid, keeping it confined to a single scene in the middle of robbing the bank. The townsfolk are being held prisoner in the bank while Joe clears out the cash. After Steve pinches Reverend Gribble’s watch, Ned makes Joe begin to transcribe the letter he wishes to send to Premier Berry in Melbourne. Thus, Joe is relegated to little more than Ned Kelly’s PA in this scene. Apart from the odd nod to moments that happened, this sequence is completely inaccurate.

In True History of the Kelly Gang, Jerilderie is a moment of absolute absurdity. Beyond it being in the snow, and the bank being attached to the printing office, we see a group of pallbearers inexplicably carrying a coffin past the scene, as Joe, dressed in hotpants and a sheepskin jacket and not much else, writhes around on the ground. To state the obvious, there is no resemblance to history in this depiction.

Betrayal

Aaron Sherritt’s betrayal is a mainstay of most interpretations of the story, as his murder is one of the few major crimes actually committed by the gang.

In the 1970 film, Aaron is caught out when Joe spots him spying on his mother’s house with police. It takes no further convincing to get this version of Joe to turn, and he bitterly states that it explains all his new clothes. This truncated version works for the limited runtime, but there’s something a bit empty about how overly simplified it is.

In 1980, however, the betrayal is built up more, culminating in Joe being informed by his girlfriend that Aaron was with a policeman in he pub where she works. This moment is played melodramatically with turbulent wind and intense music while Joe scowls and thrashes around in fury. He announces that the “bastard Sherritt” has got to die. Up to this stage Joe had been reluctant to believe Aaron would betray the gang and was acting as a double agent. This is much closer to the history but requires time to play out, which the mini series format luckily allowed.

The 2003 version depicts Aaron’s betrayal as a result of police brutality. Again, Joe’s girlfriend is the one to tell Joe that he’s up to something. Joe and Ned inform Aaron that they are going to rob the bank in Beechworth and then wait to see if police arrive. When they do, the outlaws know Aaron is the traitor and decide he has to die.

True History of the Kelly Gang, because it omits Aaron entirely, loses this vital part of the story. It was Aaron’s death, or at least the gang causing a scene at Aaron’s hut, that was to lure the police out on a special train. By removing Aaron and the rest of the sympathisers, the 2019 film completely changes the dynamic that drove the escalation in the gang’s activities.

In reality, Aaron had been working with both sides. Assisting the police paid his bills, but also gave him an opportunity to keep the police distracted so that the gang could move around undetected. Aaron actually had an agreement with the chief commissioner that if he could get Joe to turn himself in, and betray the other three, then Joe’s life would be spared. Joe frequently tested Aaron’s loyalty, in a manner very similar to that shown in the 2003 film, but as in the 1980 and 2003 depictions, it was Maggie telling Joe about Aaron’s betrayal that sealed the deal.

Murder of Sherritt and Glenrowan

1970’s depiction of the murder of Sherritt is abrupt, to say the least. We see Aaron in his hut with his head on his wife’s lap, the mother-in-law nearby, when there comes the knock at the door. We hear, “It’s Anton Week; I’ve lost my way,” then Aaron gets up and answers the door. Aaron jokingly asks Anton if he’s lost and then after a confused “Ja,” we see a shotgun poke out from under the German’s arm and blast Aaron in the chest. Aaron falls wordlessly and Joe sprints away into the night.

At Glenrowan, Joe arrives in the morning and informs Ned that Aaron is dead. His demeanour throughout the sequence is more boredom than grief, only perking up during the dances. He is depicted in the same costume that he has worn for most of the film, with an oilskin over the top. We barely see anything of him throughout and when it gets to the final shootout it becomes difficult to keep track of which one he is due to the darkness and the fact that his costume looks almost identical to Ned’s.

The Last Outlaw fares much better in both the murder and the Glenrowan depictions. The scene in Aaron’s hut matches the historical account almost exactly. Aaron opens the door to direct Anton home when Joe pushes the German away and blasts Aaron twice in the chest. Aaron falls silently (but dramatically) and Joe grabs his wife, Belle, and orders Dan be let in from the other door. All of this is almost to the letter. There is a brief moment of Joe trying to get the police out of the bedroom, and the scene ends with Joe firing into the ceiling and ordering the police out. The sequence has obviously been truncated for pacing reasons, but the way the scene ends is a little bizarre and very melodramatic. As far as historical accuracy goes, it remains faithful enough to the reality that it conveys an authentic, if not entirely accurate, representation of what happened.

Joe and Dan are depicted as arriving at Glenrowan some time in the middle of the day. Joe is morose and haunted, quickly downing whiskey to steady his nerves. The only thing that is wide of the mark is that we don’t really see Joe interacting with Ann Jones or engaging in the dancing. When it comes to the siege, we see a reckless and defiant Joe in action. He seems to be fuelled by liquid courage and anger. He is shot in the leg and falls against the outer wall before being transferred inside. Once inside his movement is unrestricted and he merely limps slightly to get around. In reality, Joe’s wound was severe enough that he could only crawl to get around.

The 2003 depiction of Sherritt’s murder is highly fanciful, without any clear motivation as to why. Aaron is shown losing at cards to the police in his hut before going to bed with his pregnant (thirteen year-old!) wife. A flutey voice is heard in the night calling for Aaron and the police surmise it is one of his “whores”. When Aaron goes out he is confronted by Joe on a distant hill dressed in unconvincing drag. Joe shoots Aaron in the chest with a shotgun and leaves him dead in the mud before rejoining Ned on horseback.

At Glenrowan, Joe is stern and business-like, as in the Jerilderie scene. He is dressed in a long grey overcoat, and white crocheted scarf, reminiscent of how the historical Joe was dressed while remaining distinctly unique to this interpretation. Joe discovers that Thomas Curnow has escaped and raises the alarm to Ned. Obviously this is a huge divergence from history as Curnow had been allowed to go home by Ned personally, and Joe had been with him at the time. When the siege unfolds, Joe goes from nervous to hysterical with terror, giggling when the circus monkey is shot, to absolutely traumatised. He staggers around with not an ounce of fight left in him.

True History of the Kelly Gang’s overly stylised depiction of Glenrowan has almost no resemblance to reality, least of all in the depiction of Joe. Here Joe walks around in a lacy pink dress with black and white warpaint, his long hair partly tied back and a durry hanging limp from his lips. He bosses Thomas Curnow around and acts as Ned’s enforcer. As Ned prepares for battle, it is Joe that gaffa tapes Ned’s memoirs to his bare torso and kisses him. When the gang realise that the train hasn’t crashed, they retreat to the inn and Joe vomits on the floor in terror. For some reason they never don the bulletproof armour and they all are quickly drenched in blood (though it is unclear where from).

Death

Joe Byrne’s death is well recorded thanks to witness accounts. At around 5:30am on 28 June 1880, Joe toasted the Kelly Gang and was almost immediately after killed by a bullet to the groin. He bled out and was dead almost immediately.

In the 1970 film, Joe gets thirsty after ducking around the bullet-riddled bar room. He pops up to grab a drink and is shot by a tracker. He mumbles, “oh, shit,” and falls. What ought to be a serious moment ends with an odd comical note.

In The Last Outlaw, Joe hobbles to the bar and pours a drink. Ned appears in the doorway and Joe responds in awe, as if this was a sign they were saved. He aggressively toasts the gang and a barrage of bullets strikes him. He awkwardly slumps to the floor as Ned dramatically screams his name. Later we see Father Gibney find his corpse.

In the 2003 film, Joe, as in the 1970 version, takes a break to have a drink. However, in this version Joe is clearly rattled by the carnage around him and wanders through the bar with a thousand yard stare. He pours his drink and leans back only to have the glass explode from a bullet and then cop a bullet through the gap in his armour. There is no toast. He stares in bewilderment then slides awkwardly down the bar and dies.

The 2019 film never actually shows Joe dying. We see him drenched in blood, whose is never made clear, and he abuses Ned for getting them into the situation. That is the last we see of him before the inn goes up in flames.

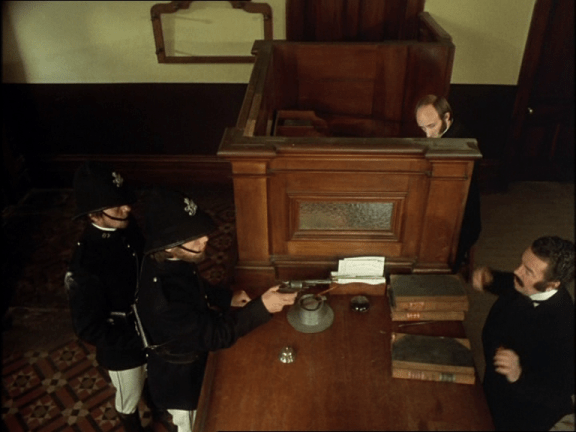

Grisly Display

It wasn’t until 1980 that any production attempted to recreate Joe Byrne’s body being displayed for photographers and onlookers at Benalla police station. Steve Bisley’s costume is almost 100% accurate, and his posing is as close to that visible in the photographs as we are likely to see. The recreation of the lockup is pitch perfect, and the whole scene with the onlookers and the photographer is, again, as accurate as you are ever likely to see in a recreation. Helen rushes through the crowd and stares in horror at the two-day-old corpse of her lover. The makeup accurately depicts the discolouration and scorch marks that are partly visible in the historical images. It is impossible to find a reasonable fault in the way this scene was portrayed.

Though a similar scene was planned for the 2003 film, True History of the Kelly Gang is when we next see a display of Joe’s body. However, in this version he is roped to a tree while poncho-clad police pose next to the corpse as if for a camera. If any attempt at historical accuracy had been employed in the costumes and location, no doubt this could have been a very impactful shot, but it is hampered by the fact that the only aspect of this that is accurate is that the body was strung up for photographs.

Conclusion

If it comes down to a matter of ranking the portrayals, the above criteria must all be factored in. Ultimately, there is yet to be a fully accurate depiction of Joe Byrne, encompassing his personality, appearance and the facts of his life with attention to complete historical accuracy, which is a shame.

Ned Kelly (1970) – 3/5

Mostly accurate on a very basic level, but the characterisation is so superficial as to miss nearly all of Joe’s personality including his sense of style, his hedonism, and gift for language. Instead we only see the boyish, larrikin aspect of Joe, which is oddly lacking in most other depictions.

The Last Outlaw (1980): 4/5

This remains the best on-screen Joe. Bisley resembles the historical Joe closely in appearance and personality. However, this Joe is played fairly safe, with his alcoholism and drug use notably absent. The decision to portray him as the murderer of Constable Scanlan is problematic, but not egregious enough to damage an otherwise fairly accurate depiction of Joe’s outlaw career.

Ned Kelly (2003): 3/5

This version of Joe goes to pains to portray him as sombre, intelligent, and a lothario. There are many notable inaccuracies in the portrayal, such as his relationship with Ned pre-dating Ned’s prison sentence, and dressing as a woman to lure Aaron Sherritt to his doom. When the odd historically accurate detail appears it almost seems accidental, yet it happens enough to give some degree of merit to the portrayal.

True History of the Kelly Gang (2019): 1/5

The only things stopping this getting a zero are the inclusion of Joe’s opium use and Sean Keenan’s engaging performance and physical resemblance to the real Joe. Everything else from the inexplicable costumes, to this version’s apparent obsession with donuts, is so far off the mark that the character could go by any other name and nobody would recognise it as an attempt to portray Joe Byrne. The fact that any resemblance to the real Joe is apparently accidental would otherwise be enough that it should not even rate a mention as a portrayal of Joe Byrne. A horribly squandered opportunity to utilise a superb casting choice to portray this historical figure accurately.

My Irish gg grandmother Mary Foran was friends with Joe Byrne’s mother and family. They both came from County Clare. They all came out on the Thomas Arbuthnot from Ireland during the Great Famine in 1850. Like my gg grandmother Joe Byrne’s 16 yr old mother Margaret White, could read and write (most orphaned girls couldn’t) and was sent to a rural area to work as a house servant for which she was paid? 7- 8/ for two years. She married Patrick Byrne of Co Carlow, and they settled in Victoria where they had six children. Mary was also friends with other gang mother, Bridget Young from Co Galway. Bridget married Richard Hart and settled in Wangaratta, Victoria, and their children included Steve Hart (b 1859). The family were prosperous farmers with a lot of lands. Mary married my gg grandfather Edmund Mellor, a wealthy steamboat company proprietor.

A bit of family trivia about Joe Byrne’s family. My gg-grandmother 16yr old Mary Foran was friends with two of the Kelly Gang mothers. They all came out on the Thomas Arbuthnot from Ireland during the Great Famine in 1850. Joe Byrne’s 16 yr old mother Margaret White, came from Co Clare. She could read and write and was sent to a rural area to work as a house servant for which she was paid? 7- 8/ for two years. She married Patrick Byrne of Co Carlow, and they settled in Victoria where they had six children. The other gang mother was Bridget Young from Co Galway. Bridget married Richard Hart and settled in Wangaratta, Victoria, and their children included Steve Hart (b 1859). The family were prosperous farmers with a lot of lands. Mary married my gg grandfather Edmund Mellor, a wealthy steamboat company proprietor. Cheers John

Sent from my iPhone

>