After his release from Pentridge Prison, Andrew George Scott struggled to get back on his feet. While he may have been determined to right the wrongs of his past, the police were seemingly determined to stifle those efforts. Scott was kept under constant police surveillance in the hope that at some point he would slip up. This harassment came to a head in several well publicised incidents.

[Source: “NEWS OF THE DAY.” The Age (Melbourne) 16 July 1879: 2.]

On 9 July, 1879, it was claimed that three men attempted to instigate an escape from the Williamstown battery of 19 year-old William Johnson, alias Andrew Fogarty, who was doing a two year sentence for housebreaking. Scott, Nesbitt and Johnson had done time together in Pentridge, their sentences overlapping from 5 April to 11 April, 1878, whereupon Nesbitt was transferred to Williamstown where convicts were housed in the old military barracks at Fort Gellibrand and employed upgrading the batteries. After Nesbitt was transferred, Johnson and Scott remained in Pentridge together until Scott’s release on 18 March, 1879. It was alleged that one of the men broke open a window and tried to give Johnson two revolvers to help him escape. Ultimately, the men disappeared and no escape was ever undertaken, but police immediately assumed Scott’s guilt. The press, naturally, leaped upon the story as evidence that the notorious Captain Moonlite was preparing a gang.

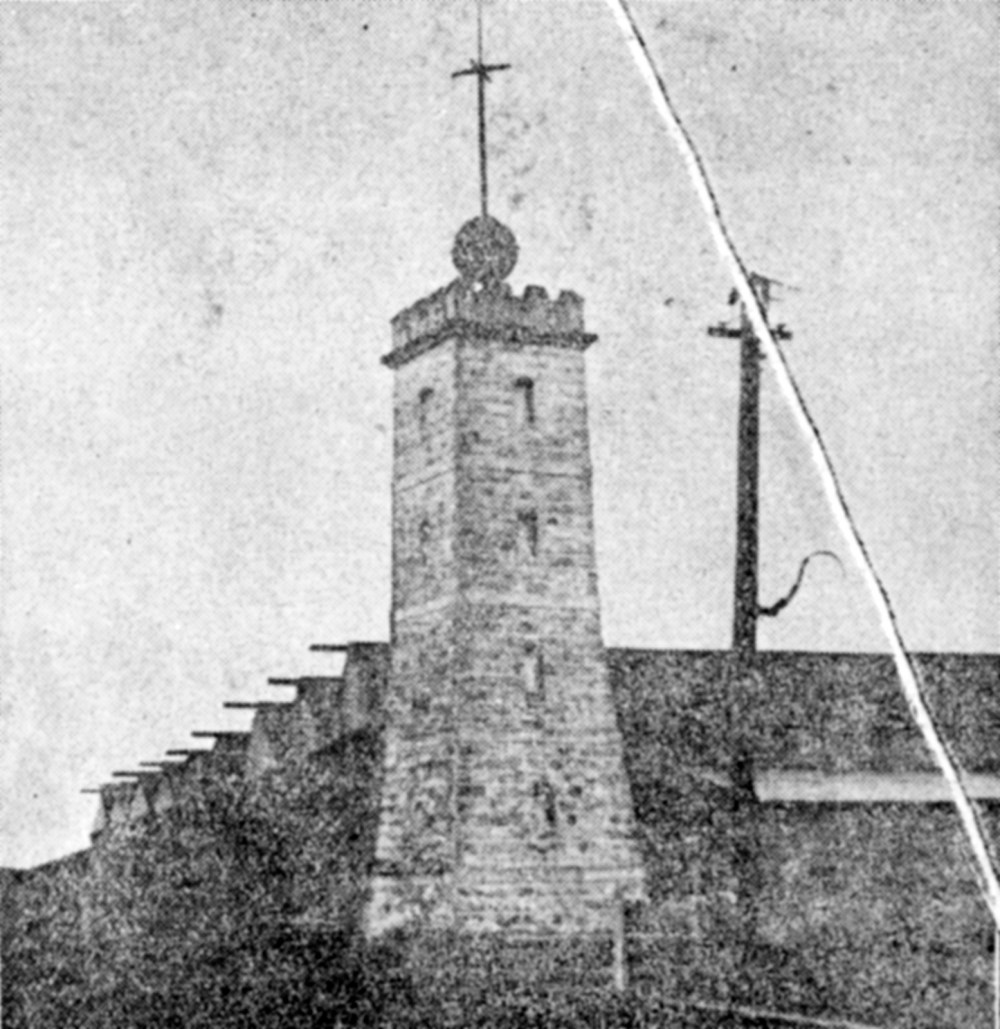

The Williamstown Timeball Tower c.1870s [Source: State Library of Victoria]

At the time, Scott and Nesbitt were in town looking for a venue in which Scott could give a presentation of one of his lectures on the need for prison reform. The lecture series had been a source of both pride and humiliation for Scott as audiences had responded overwhelmingly positively, but as the performances grew in popularity the police began to crack down on them, causing several events to be cancelled. There remained a question over the motivation for such a heavy-handed response to the lectures – was it merely an effort to prevent slanderous lies from being given a platform or was it censorship to obscure the truth of the allegations?

Scott was keenly aware of something of a smear campaign being launched against him and he was being touted as the murderer of an actor named Francis Marion Bates, who was found dead and looted in Melbourne. A man supposedly fitting Scott’s description had been seen following Bates shortly before he disappeared. After an inquest was held, it would be established that Bates had not been murdered at all, but had died of congestive heart and lung failure. Unfortunately for Scott, the general public had already been led to believe it was an open and shut case with blood on Scott’s hands. All he could hope for was that the public’s notoriously short memory would see the claim forgotten once his name was cleared in the matter.

William Johnson [Source: PROV]

The Williamstown battery was not much of a gaol by any stretch, only holding 18 prisoners at the time (one of which acted as the cook) and was merely a wooden building with plastered interior walls. The barracks had never been intended to house convicts and its rather flimsy construction had not weathered the conditions on Hobson’s Bay well at all. At night there was no guard on duty, but there were three warders on staff: Henry Steele, the senior warden; Turner and Robert Durham. At 8pm Steele headed off to his home on Twyford Street, leaving Durham in charge. The gaol was separated into three parts: the warder’s room, where the staff slept; the prisoner’s dormitory; and the kitchen, where the cook resided. Durham did the final inspection at 10pm and saw nothing awry. When Turner returned on the last train from Melbourne, he arrived at the barracks at 12:30am and went straight to bed. Durham retired soon after. At 1:30am Durham and Turner heard a knocking at the warder’s room and prisoner’s dormitory. Durham got up to investigate and was informed by William Johnson that there was rain coming in through a window about three feet above ground level. Durham got onto Johnson’s bed and saw that the window appeared to have been jimmied open, but not enough to allow a person in or out, and the fastenings appeared to have been cut with a knife. It was at this point that Durham recalled that he had seen a group of four men or boys loitering around the railway station and battery reserve at 2pm the previous afternoon, which he later asserted had looked like they were up to no good. He would swear that he recognised Andrew Scott and James Nesbitt walking to the beach and out of view. The prisoners had, at that time, been working on the reserve and Durham would recall seeing Johnson leave his cart to go to where the two men had disappeared. Durham was on it like a fly on a fresh cowpat, but could not reach them before Johnson returned to work. Durham spoke to the two men and said they had no right to speak to the prisoners, to which the man he identified as Scott replied, “This is a public road, is it not?” Durham had reported the incident to Steele when he had returned at 6pm but until the apparent attempted break in he had put it out of his mind.

With things settling down at the barracks, Henry Steele learner of the incident and reported it to the Williamstown police. The suggestion that the notorious Captain Moonlite was involved prompted a speedy response and a warrant was quickly issued. At the time the offence was being reported, Scott and Nesbitt were on foot and travelling to Clunes via Buninyong. When they arrived in town on the 17th they turned themselves in. Two revolvers Scott had allegedly disposed of had been found and were kept by the police as evidence. At the same time police had been warned to make sure their weapons were in good working order and arrangements were being made to send Johnson back to Pentridge.

Scott and Nesbitt, safely in custody, were sent to Melbourne to await trial with a supposed associate named Frank Foster, alias Croker, and kept in the Swanston Street lock-up. Foster had been named during initial investigation and was arrested at Talbot the day after Scott and Nesbitt turned themselves in. Foster had been serving a six year sentence in Pentridge for housebreaking at the same time as the others, but had gained his freedom in 1878 after a petition from the people of Talbot had been lodged to the government. Foster, it appeared, had been wrongfully imprisoned for the preceding five years after being framed. Yet, as far as the police were concerned Foster was guilty, they just hadn’t found a crime to pin on him yet. Associating him with Scott meant they finally had an opportunity to put him away without any pesky interference from do-gooders setting him free.

When questioned after his arrest, Scott’s name was cleared in relation to the Bates case when the two key witnesses actually saw Scott in person and emphatically denied he was the man they had seen. Typically, this was a fact most of the press tried to gloss over, eager to foster the image of Scott as an arch-fiend. Scott requested that he be furnished with the evidence supposedly collated against him and his associates in the Williamstown incident, but Detective Mackay, who was in charge of the investigation, refused to do so. The trio were remanded to Williamstown on Wednesday, 23 July, and a hearing was set for the Friday. No doubt it was an anxious wait for the men.

Frank Foster [Source: PROV]

On 25 July, Scott, Nesbitt and Foster appeared at Williamstown Police Court, charged with unlawfully conveying a pistol into the gaol at Williamstown battery. They were represented by Mr. Read, with Sub-Inspector Larner appearing for the prosecution. Henry Steele, Robert Durham, Edwin Robinson (son of the battery-keeper), and a prisoner named William Baker appeared to give evidence for the prosecution. Baker stated in his evidence that Scott, accompanied by Nesbitt and another man, had knocked on a window asking for Fogarty (Johnson’s alias) and was directed to the correct spot, whereupon he opened the window and gave Johnson a revolver. Johnson then allegedly refused to take it out of fear and Nesbitt spoke threateningly about the guards before they left. An interesting element of Baker’s testimony was that while all other witnesses claimed that it was raining that night, Baker claimed the weather was clear and dry.

Johnson also provided evidence. He confirmed that on the afternoon of the 9th he absconded work to speak to Scott and Nesbitt, but couldn’t confirm that they had any involvement with breaking open the window. More compelling was Johnson’s confession that his previous evidence to Detective Mackay was a string of lies that he was under pressure from his charges to swear, being constantly threatened while the investigation was occurring. He claimed that the fear of reprisals from the warders at the gaol was what motivated him to perjure himself, and it was a gang of larrikins that had jimmied his window open, and no revolver was ever passed through. As important as the evidence was, the bench determined that Johnson was an unreliable witness and he was removed from the box.

Further thickening the plot was the testimony of a fellow inmate named McIntosh, whose bed was closer to Johnson’s than Baker’s, in which he stated he could not verify who the men outside were and that the object passed through was a chisel, not a revolver. A pawnbroker named Ellis also testified that he had sold two revolvers to Scott, but they were larger than the ones produced as evidence. A lad named Patrick McMullen testified that Scott had asked for a form to give him permission to see Johnson, which had been presented when the encounter at the Battery Reserve occurred. Rev. Lewis, a clergyman from Blackwood, testified that Scott had given him a pair of revolvers, and a Blackwood Senior Constable named Young also testified that he had seen the defendants in the area on 13 July, corroborating the reverend’s evidence.

James Nesbitt, alias Lyons [Source: PROV]

The hearing was over quickly with Mr. Read addressing the court by stating that as the object allegedly passed through the window could not be verified, and since the Williamstown Battery was not an official gaol in the legal sense, and there being no compelling evidence that an escape had actually been attempted, the complaint could not be sustained. The bench was inclined to agree and the defendants were acquitted. The result caused a response from onlookers that the men, and indeed the furious prosecution, could hardly have expected – applause. If ever there was a sign that the general public in Victoria were becoming disenfranchised with the police, surely this was it. Yet, however much the hoi polloi had their distrust of authority, it was incomparable to that of Scott, who had endured insult and injury at the hands of the police, and with two charges they had laid against him having fallen through he knew it was only going to get worse.

The economic depression in Victoria proved to be a sore point for the Berry government, with calls made for action to help those affected, and the press being forced to admit that unemployment was not merely the result of lazy people refusing to work. [Source: Mount Alexander Mail, 25/06/1879, page 2]

For months civil unrest had been brewing due to an economic depression that was hitting Victoria hard. Rallies in the cities were held and workers battled for their rights. Outside the cities, swagmen tramped the countryside looking for work, and now Andrew Scott – former engineer, soldier, and clergyman – found himself in that same sinking boat along with James Nesbitt, Thomas Williams and Gus Wernicke. No doubt it came as no big surprise that when a bank robbery was carried out in Lancefield, Scott and Nesbitt were blamed, despite being nowhere nearby.

At 10:10am on 15 August, two men entered a branch of the Commercial Bank of Australia at Lancefield. One presented a revolver and ordered Arthur Morrison, the accountant, to stay quiet or he would be shot claiming that the two robbers were members of the Kelly Gang and had locked up the police. Morrison was then bound with ropes and gagged with a piece of wood. With one robber keeping watch, the other took as many coins and notes as he could carry. When a customer named Charles Musty accidentally interrupted the robbery, he too was bailed up. Ironically, had the robbers ordered Musty to hand over his cash they would have gained an additional £200. While all this was happening, Zalmonah Wallace Carlisle, the manager, was blissfully unaware as he enjoyed the fresh air in the garden in his way to the post office. Within a few moments the damage was done and the robbers had fled with £866 9s 4d. The initial report to the police stated that the two offenders matched the description of the outlaws Ned Kelly and Steve Hart. In response to this Superintendents Hare and Sadleir, who were in charge of the hunt for the Kelly Gang, were sent out to Lancefield accompanied by Sub-Inspector O’Connor and his Queensland native police. It soon emerged that the crime had not been committed by the Kellys at all and there were only two other men that police suspected of the crime.

Once again, Andrew Scott and James Nesbitt were hauled in by the police. They were questioned about their whereabouts during the robbery. Scott and Nesbitt had no hesitation in stating they had been in Melbourne the whole time. Upon further investigation the alibi was solid and, much to the chagrin of the police, the pair were released.

This was the last straw for Scott. He decided that Victoria was only a place of misery for him and his companions and their fortunes lay north in New South Wales. He informed police that he intended to leave the colony in the hope that they would cease haranguing him. Taking all he could carry in a swag, Andrew George Scott, the man popularly known as Captain Moonlite, headed off in search of greener pastures accompanied by his partner James Nesbitt and their friends Frank Johns, alias Thomas Williams, and Augustus Wernicke. They would never return.

As for William Johnson, the young man at the centre of the Williamstown incident, immediately following the acquittal of Scott, Nesbitt and Foster he was transferred to Pentridge. He would remain in and out of prison until January of 1883.

Regarding the Lancefield bank robbery, it would later transpire that the robbery had been undertaken by two men named Cornelius Bray and Charles Lowe. Bray would claim he was desperately seeking work and fell in with Lowe who told him he could guarantee him employment. He then claimed he was forced to participate in the robbery on pain of death if he refused. Lowe responded that Bray was merely trying to paint him blacker than he was in order to gain sympathy. The pair were found guilty, Bray receiving five years hard labour and Lowe receiving eight years, the first to be carried out in irons.

***

“Numerous petty insults were given us by the police. I honestly felt I was unsafe in Victoria. I feared perjury and felt hunted down and maddened by injustice and slander. I left Melbourne with my friends, carrying my blankets, clothes and firearms. I felt rabid and would have resisted capture by the police. Though I knew I had committed no crime, bitter experience had taught me that innocence and safety from accusations were different things. My life and liberty had been endangered by perjury and … they would be endangered till I could secretly escape from those who seemed to hunger, if not for my blood, for my liberty and safety.”

– Andrew Scott