It’s hard to believe now, but there was a time when Stephen Hart was once one of the most infamous bushrangers in Australia. Now he is often thought of as no more than an also-ran, an afterthought, the “other Kelly”. According to an article in the Evening News, Sydney, 14 February 1879, “Ned Kelly is looked upon as a hero all over the North-eastern district, and Steve Hart is second only in popular esteem.” So what changed the public perception of one of only four people ever outlawed in the history of Victoria? What led to Steve Hart becoming the forgotten Kelly Gang member?

To understand the story of Steve Hart, we must look at his parents. Steve’s father Richard Hart was transported to Australia as an eighteen year old convict in 1835 on the Lady McNaughton for being a pick-pocket. Earning his ticket of leave on 26 January 1840, he would later gain his Certificate of Freedom on 18 June 1843. In the subsequent years he would be joined by his sister Anne and brother Richard, both were transported as convicts. Richard was employed at Gunning Station at Fish River working for Elizabeth O’Neill, the widow of John Kennedy Hume, brother of explorer Hamilton Hume, who had been murdered by bushranger Thomas Whitton on 20 January 1840. The widow Hume had been left with nine children to care for (she was pregnant with her ninth at the time of the murder) and nobody to protect them, so Richard’s presence was likely very welcome.

Ten years after Richard gained his ticket of leave, recently orphaned Bridget Young, aged sixteen, and her sister Mary, aged twenty-one, travelled to Australia from Galway on the Thomas Arbuthnot as part of the “Earl Grey Famine Orphan Scheme“. No doubt the potential opportunities in Australia were a glimmer of hope as they escaped the crushing existence of being employed at workhouses back in Ireland and trying to stave off starvation due to the Great Hunger, also known as the Great Famine or the Irish Potato Famine. They arrived in Sydney and were stationed at the Hyde Park Barracks for several weeks before travelling to Yass for work, Bridget then became indentured to Mr. Smith of Mingay Station in Gundagai, which was one of the various stations affected by the horrendous flood of June 1852.

One of the young women who had accompanied Bridget all the way to Yass since their initial departure from Galway on the Thomas Arbuthnot was Margret White, who would later move to Goulburn where she would marry Paddy Byrne. These two were the parents of Kelly gang member Joe Byrne. What interaction these women had, if any, remains an unanswered question.

When Elizabeth O’Neill left Gunning and took up residence at her property Burramine (aka Byramine) at Yarrawonga in the 1850s it is likely that Richard travelled with her. By this time, Richard had met Bridget Young and the pair were raising a family in Gundagai, but a short time thereafter the family arrived in South Wangaratta where they soon established themselves, possibly with more than a little assistance from Elizabeth.

Stephen Hart was born at the Hart property on Three Mile Creek, Wangaratta, on 4 October 1859 to Richard and Bridget Hart (née Young), and baptised on 13 October that year. Steve was one of thirteen children. His siblings were William (who died as an infant in Gundagai in 1852), Ellen, Julia, Richard jr (Dick), Thomas Myles, Esther (Ettie), Winifred, Agnes, Nicholas, Rachel and Harriet – certainly Richard snr and Bridget had their hands full with such a brood. Steve’s was not an overly troubled childhood by the standards of the time and place. In fact the Hart family seemed to be quite well to do with a 53 acre property in Wangaratta on the Three Mile Creek and a larger 230 acre block at the foot of the Warby Ranges. As with all selector’s sons, Steve was expected to work on the selection as soon as he was old enough but he had at least some education and could read and write.

Steve was an able, if not necessarily dedicated, worker. Employed for a time as a butcher boy in Oxley to a Mr. Gardiner, Steve soon ended up working with his father and siblings stumping properties for what would have been around £6 a month. Hardly glamorous work, but honest. No doubt he was frequently roped into doing jobs for the Bowderns who were neighbours to the Harts and close friends.

As a teenager, Steve was a jockey who had a few minor prizes under his belt including the Benalla Handicap. His small frame and natural affinity with horses made him the perfect fit and would come in handy later on when combined with his excellent geographical knowledge of Wangaratta and the Warby Ranges. He was evidently a popular youth, quite likely due to his fun loving nature and eagerness to please. It’s easy to imagine Steve strutting past O’Brien’s hotel with his hat cocked, chinstrap under his nose and a bright sash around his waist accompanied by the likes of Dan Kelly, Tom Lloyd, John Lloyd and, later on, Aaron Sherritt, Joe Byrne and Ned Kelly. His time with the Greta Mob, as they called themselves, was probably the only time Steve felt a sense of belonging, his adolescent mind far more preoccupied with socialising than work. It seems he built a strong bond with Dan Kelly in particular during this time, perhaps drawn in by the self-assuredness and natural charisma the younger Kelly seemed to possess. The Kelly boys were seemingly blessed with the ability to leave a favourable impression on most anyone they met while also projecting a ‘don’t mess with me’ vibe likely forged due to their harsh upbringing. In contrast, Steve’s slender build and delicate features likely made him someone who was far from intimidating, so being around someone like Dan would have been a good move to make him tougher by association. The Greta Mob were larrikins and what Steve lacked in physicality he made up for in horsemanship – a primary interest of the larrikin class. The gang were fond of showing off their skills on horseback and this kept them in the cross-hairs of the local police.

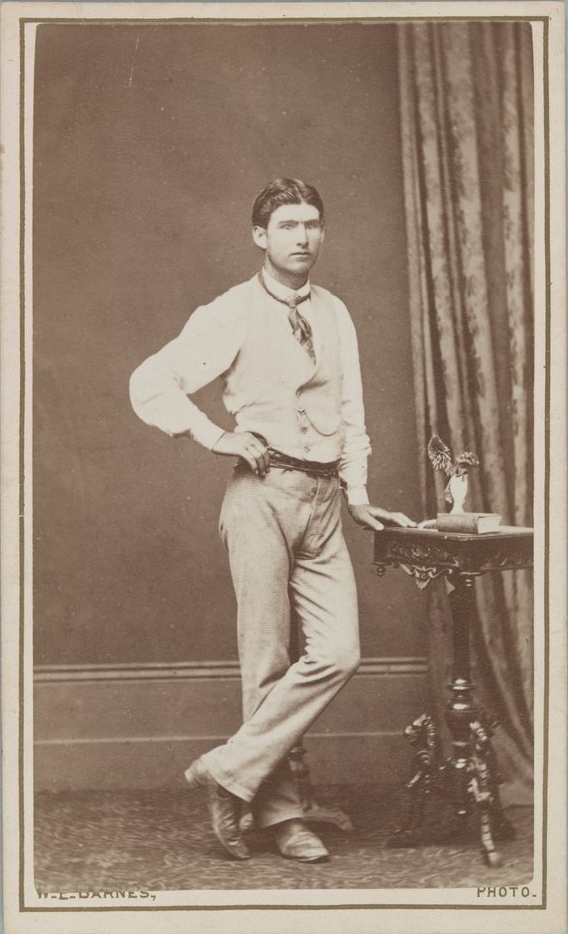

Of course, Steve was not exempt from the seemingly obligatory prison stint. On 7 July, 1877, Steve Hart appeared in Wangaratta Police Court during the general sessions charged with stealing a horse from David Green of Glenrowan. Green’s grey mare had gone missing and Sergeant Steele had been tasked with finding the culprit. Going to the Hart property in Wangaratta, Steele interrogated Steve and a lodger named James O’Brien about the horse in the paddock behind them. “What, that grey mare?” Steve asked incredulously. Steele pressed the point and Steve indicated he had been loaned the horse from a man in town. When Steele asked for a name, Steve replied “Have you a warrant for me? I’ll give you no bloody information unless you have.” Steele promptly arrested Hart and O’Brien, who had also gotten Dick Hart implicated in a horse theft at the same time. The initial charge of theft was altered to ‘illegally using a horse’ and Steve was shortly convicted and sent to Beechworth Gaol for twelve months. It was here that he befriended Dan Kelly who was doing time over an incident at a shop where he had gotten drunk and broken in. The freezing winter months and stifling summer heat would have taken their toll on the lad, then just eighteen. Undoubtedly this would have made him seem rather a black sheep in the family by the time he got home, so instead of staying at the farm he left to find work elsewhere, first supposedly shearing in New South Wales and later at a sawmill near Mansfield before he joined the Kelly brothers at their gold claim on Bullock Creek. It was honest enough work and no doubt his body had been bulked up from the hard labour smashing granite with a hammer in Beechworth Gaol for a year. The one known photograph of Steve depicts him as a slender youth, but descriptions of Steve in 1878 painted a different picture.

After Steve’s exit from Beechworth Gaol and all during his time travelling for work, Sergeant Steele had been hounding his family for word on his whereabouts. Steele was convinced he was off duffing stock with the Kellys and even threatened the Harts that if they didn’t tell him exactly where Steve was that he’d be shot. Unfortunately the family had no idea of Steve’s whereabouts.

When Constable Fitzpatrick was assaulted at the Kelly house in April 1878, Steve was not involved. However he was reported to have made the decision to stick by his mates and while working with his father and siblings he downed his tools and took off declaring:

“A short life, but a merry one!”

This phrase not only summed up the youthful impulsiveness of the adolescent Hart, but became a sort of catchphrase for the Kelly gang later on when the meaning had far more sinister undertones. Though, it was usually attributed to Steve, there is some question over the accuracy of the attribution, though it certainly sounds authentic enough to be believable and has become the phrase that is synonymous with him.

Steve was with Dan and Ned in October 1878 when a party of police had entered the Wombat Ranges hunting for the two Kellys. On 26 October Ned Kelly led Dan, Steve and Joe Byrne in an assault on the police party. Three police were killed in the incident, though Steve was not one of the killers. When McIntyre escaped on horseback Dan Kelly had directed Steve and Joe to catch him. They had gone a distance into the bush but could not catch up. They fired ineffectually into the bush. No doubt this episode was traumatic for all involved, but for Steve and Joe, who came from comparatively sheltered lives compared to the Kelly brothers, it must have been doubly so.

The immediate aftermath of Stringybark Creek saw the gang desperate to escape capture long enough to establish a new base of operations. This was where Steve Hart had his chance to shine. Navigating the torrential flood waters that caused the rivers to swell to insurmountable levels, Steve took the gang into his playground. Crossing a secluded bridge he took the gang and their horses safely to Hart territory, successfully evading the police search parties. Steve would prove invaluable to the gang in their next undertaking – the robbery of a bank.

An oft related anecdote is that Steve Hart, dressed as a veiled woman riding side-saddle, would ride into towns close to the Strathbogie and Warby Ranges to gather information about the banks. On one of these reconnaissance missions Steve found the perfect target in the township of Euroa. Disguises were not a necessity for Steve at this stage as he was the only member of the gang yet to be identified.

Steve’s role in the bank robbery was straightforward but vital. When Ned and Dan set out from Faithful’s Creek, Steve rode ahead on his bay mare. Arriving in town in advance of the others, Steve got a bite to eat while he waited and used the time to assess whether the plan was still viable. When the others arrived he accompanied Dan around the back where he went into the bank manager’s residence and locked Susy Scott, her mother and children in the parlour, but not before being recognised by Fanny Shaw who was employed as a general maid for the Scotts. Steve and Fanny were schoolmates and Steve informed Fanny that he was in the process of robbing the bank before tricking her into joining the family in the parlour. Fanny Shaw’s testimony would finally expose the mysterious fourth member of the Kelly Gang. In the ashes of the fire from the gang’s old clothes was found what was believed to be a woman’s bonnet, but was after revealed to be Steve’s cabbage tree hat with a fly veil. While this would appear to indicate the cross-dressing rumours were no more than that it is very difficult to disprove the initial claim.

With the fourth member of the gang finally identified, a description was published in an effort to help the public recognise the miscreant:

He is described in the criminal records as being 21 years of age, 5ft. 6in. high, fresh complexion, brown hair, and hazel eyes ; right leg has been injured.

When the gang were officially declared outlaws it became much harder to move freely. Steve’s reconnaissance missions ended in favour of his sister Ettie feeding information back to the gang. When the raid on Jerilderie was decided upon the gang crossed into New South Wales in pairs, Ned and Joe heading for the pub where they received intelligence from Mary the Larrikin before meeting up with Dan and Steve the next day.

Steve’s role in the raids seems to have very much been as Ned’s attack dog. He was the only gang member to not don a police uniform after the Jerilderie police had been locked in their own cells. When the bank was robbed it was Steve who found the bank manager Tarleton having a bath (and subsequently made to guard him as he dressed). Witnesses in the hotel would describe Steve as seeming very nervous. While Ned was going about his work Steve stole a watch from Reverend Gribble. The outrage made it to Ned Kelly who ordered Steve to return the watch, which he did under sufferance. It must have seemed a strange paradox to be an outlawed bushranger but not be allowed to steal from people. Once again he and Dan performed horse tricks as they left the town after a victorious raid.

For months the gang seemingly disappeared. More detailed descriptions were offered that appeared to do very little to help identify the gang:

Steve Hart, about 21 years of age, 5 feet 4 inches high, dark complexion, black hair, short dark hair on sides of face and chin, bandy legs, stout build, clumsy appearance, speaks very slowly; dressed in dark paget suit, light felt hat, and elastic-side boots.

Watch parties were assigned to the Kelly, Hart and Byrne properties to stop them from returning home. During this time the banks were guarded by men of the garrison artillery, which made future plans for bank robbery impossible to carry out. But by the beginning of 1880 the gang were making appearances again, this time they were stealing metal to make suits of armour.

At Glenrowan, Steve initially attempted to pull up rails from the train track with Ned but soon became the attack dog again, keeping prisoners under control while Ned found the men who could lift the rails. Steve’s behaviour was typically aggressive, but as he was confined to guarding the women and children in the station-master’s house he became bored and took to drinking and even napped on the sofa with his revolvers resting on his chest. Depending on which account you read, at one point either Thomas Curnow helped Steve remove his boots and wash his feet in warm water to alleviate swelling or Steve ordered some of the women to wash his feet. He was also seen with his head on Jane Jones’ lap while he complained of feeling unwell. When Steve tired of being isolated he took the women and children to the inn to join the rest of the party.

When the police train was stopped and firing broke out, Steve seemed to avoid injury. However later on witnesses claimed he had injured his arm. Some witnesses described him cowering behind the fireplace to avoid gunfire, his initial overconfidence brought about by the armour supplanted by terror. After Joe Byrne’s death and Ned Kelly’s apparent disappearance Steve was despondent. When the prisoners were allowed to exit the inn he was overheard asking Dan Kelly “What shall we do now?” to which the reply was “I shall tell you directly.” Many have interpreted this to indicate a suicide pact. The truth about Steve’s cause of death will never be determined, however, as his corpse was burned beyond recognition in the fire that destroyed the inn. Stories of Steve and Dan surviving the fire are ludicrous and easily disproved.

After the fire, Steve’s body was retrieved and Superintendent Sadleir made the controversial decision to hand it over to the Hart family. A coffin was quickly procured and the remains placed inside and buried in a clandestine service in Greta Cemetery next to Dan Kelly in an unmarked grave. Steve’s untimely demise seemed to weigh heavily on the family but manifested in various ways. Ettie Hart appeared in a stage production entitled Kelly Family, whereas Dick preferred to stew over the turn of events and even agitated to form a second gang with Patsy Byrne, Wild Wright, Jim Kelly and Tom Lloyd. The agitation amounted to nothing however. In 1899, Tom Lloyd would marry Steve’s younger sister Rachel.

Over time Steve’s notoriety faded and soon he became “the other guy” in popular culture. Yet, Steve Hart is one of the more tragic characters in the Kelly saga, his youth and poor choices leading to a horrific and untimely death. There is perhaps no better example of the folly of youth than this accidental bushranger who just wanted to back up his mate and ended up one of the most wanted men in the British Empire.

A very special thank you to Noeleen Lloyd whose advice and additional information on the Hart family was invaluable in the compiling of this biography.

Selected sources:

LA citation”STEPHEN HART’S BOYHOOD.” Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 – 1954) 10 July 1880: 6.

“More Facts About the Kelly Raid.” Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931) 14 February 1879: 3.

“DESCRIPTION OF THE OUTLAWS.” Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 – 1954) 14 December 1878: 16.

“THE KELLY GANG” The Kyneton Observer (Vic. : 1856 – 1900) 8 March 1879: 2.

“WHEN GUNDAGAI WAS A TRAGIC SIGHT” The Gundagai Independent (NSW : 1928 – 1939) 1 August 1935: 6.

“Country News.” Australasian Chronicle (Sydney, NSW : 1839 – 1843) 28 January 1840: 2.

Image sources:

STEPHEN HART. The Illustrated Australian News. July 17, 1880. SLV Source ID: 1760624